Everything You Need To Know About The Zika Virus

On Monday, the World Health Organization declared the Zika virus a global health emergency after an “explosive” number of cases swept South America. The mosquito-borne virus has caused worldwide concern because of its apparent connection to microcephaly, a neurological birth disorder where infants are born with underdeveloped brains and abnormally small heads.

By declaring a state of emergency, WHO has confirmed the severity of the problem, but there is some skepticism due to the limited knowledge available and the unconfirmed link to neurological problems. While Zika is associated with microcephaly, there is no proven causation. WHO Director Margaret Chan said at a Geneva news conference that they will begin studying the connection between microcephaly and the Zika virus in the next couple of weeks. However, it could still be six to nine months before doctors can prove or disprove the connection between Zika and the neurological disorder.

“Can you imagine if we do not do all this work now and wait until all these scientific evidence to come out, people will say why didn’t you take action?” Chan said, perhaps remembering when the organization waswidely criticized for failing to act quickly against the Ebola outbreak.

Here’s what we know:

Why the panic? Zika is a mosquito-borne virus in the same family as West Nile, yellow fever, and dengue, but unlike its cousins, which cause extremely painful symptoms, Zika-related sickness is usually mild.According to the CDC, only one in five people infected will develop signs of infection. Zika’s major threat comes from its link to microcephaly, a rare condition that causes newborns to have incomplete brain development.

Brazil saw its first case of Zika in May 2015, and then suffered 20 times more cases of microcephaly than it had the previous year. CDC evidence further supports this connection, finding the virus in tissue samples from four Brazilian infants with microcephaly.

Where did it come from? The first cases were found in Uganda in 1947, but it has since caused outbreaks elsewhere in Africa, Southeast Asia, and South America. In countries where it is endemic, it’s seen as relatively benign. People may get the virus at a young age, similar to chicken pox. But in regions where the virus is rare, pregnant women are at risk of first-time exposure.

Where is it now? Many cases in South America and the Caribbean have been reported, including Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. While no one has yet contracted the virus within the United States, it appears that pregnant women have returned to the country infected. In one such case, a woman in Hawaii delivered a baby with microcephaly after being infected with the virus in Brazil. Florida Governor Rick Scott declared a state of emergency in four counties where people have been diagnosed with Zika virus. While the state reports nine cases of the virus, all nine cases were contracted abroad.

What is being done? Currently, there is no vaccine or treatment available. A consortium of American and Canadian scientists working on the vaccine recently told Reuters that the first stage of testing on humans could begin as early as August.

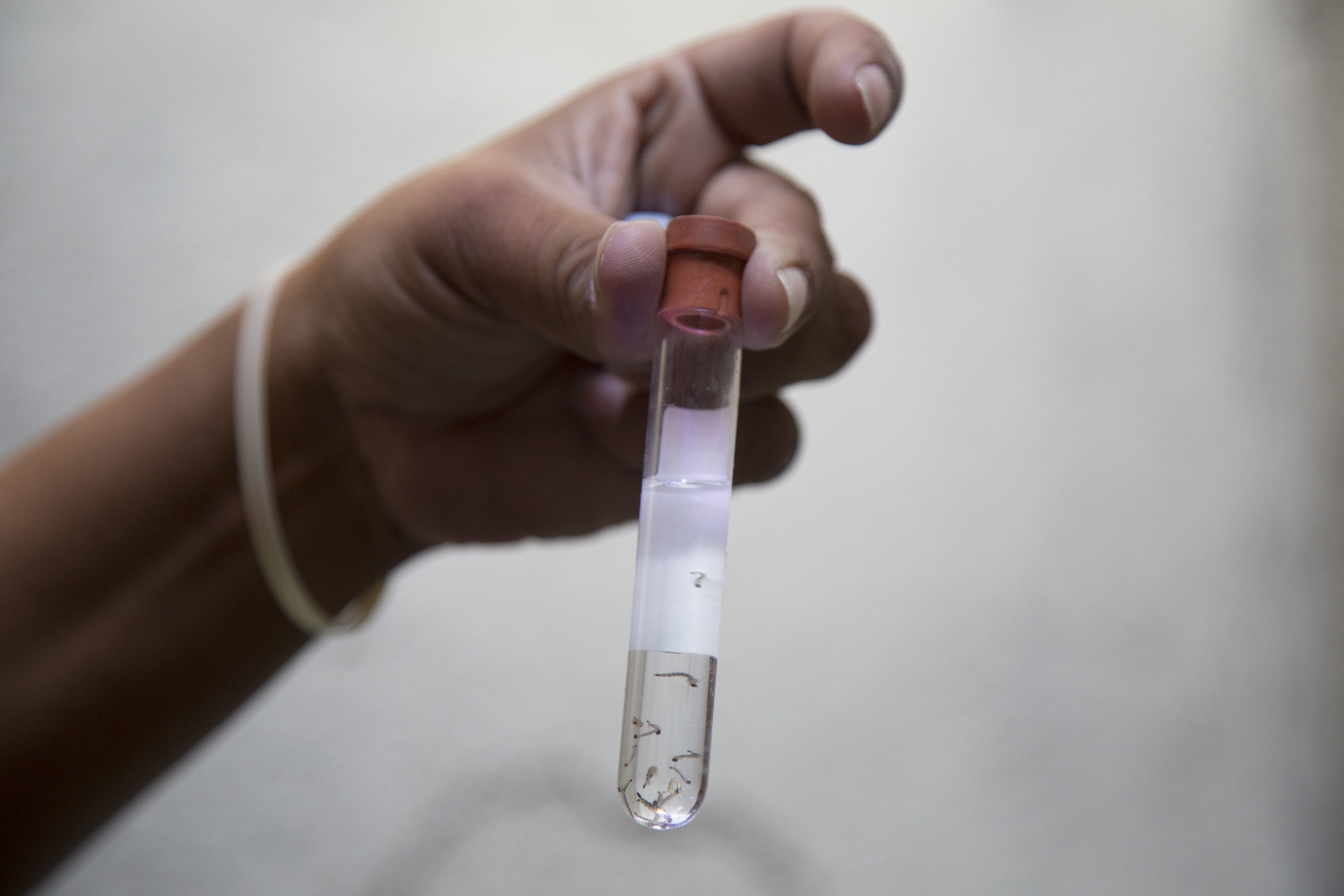

And you get it from mosquitoes? Yes, specifically from Aedes aegypti. You may know her from such viruses as yellow fever, dengue, and Chikungunya. But unlike most other mosquitoes, the female Aedes aegypti— the only confirmed carrier — feeds during the day. This means that those bed nets that were once used to protect the sleeping from malaria won’t be much help this time. Aedes also loves city life and only needs but a capful of stagnant water to breed. But new evidence supports that the virus can also be sexually transmitted. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed that the Zika virus was sexually transmitted to someone in Texas who never set foot in a Zika- exposed region.

How can pregnant women protect themselves? The CDC’s travel alert emphasizes that pregnant women should avoid traveling to any country experiencing the virus. Pregnant women in Brazil and other infected countries are advised not to go out. If they must go outside — which seems likely — bug repellent containing DEET has so far been the most effective.Officials in El Salvador and other countries have begun urging women to avoid getting pregnant until 2018, which is further complicated by the abortion dilemma in many Latin American countries. Women in El Salvador can face jail time for an abortion under any circumstance.

What does this mean for Brazil? Brazil is the most affected country in South America, with an estimated 1.5 million cases. Despite WHO declaring a state of emergency and officials admittedly struggling to destroy and prevent mosquito breeding grounds, authorities say they are still eager to host the Olympics in Rio this year. Brazil asserts that there is no risk to athletes or spectators… unless they’re pregnant. Olympics or not, the WHO designation has already turned global attention towards the Americas, and necessitates an emergency response.