More Valuable Than Money

Meta Money Peace: A groundbreaking book on how to really think about money.

The three pieces of content that I really looked forward to consuming this summer were:

- Hamilton (this was an excellent movie and didn’t disappoint and I’m glad having watched the movie to have not paid hundreds if not thousands of dollars to watch this in person as I’ve never been a theater type of person).

- Tenet (looking forward to seeing this given I’ve been a fan of many of Christopher Nolan’s other films)

- The Psychology of Money (I’ve been a fan of Morgan Housel’s writing for quite some time)

I recently read The Psychology of Money and it is a fantastic book. In fact, we predict it will be a very popular read (as it should be) and is one of the best books when it comes to thinking about money. Morgan Housel cuts through the noise, providing a 238-page read with an impressive highlight to text ratio rife with nuggets of wisdom.

People spend a lot of time thinking about money, but we really don’t think about the more crucial and fundamental aspects of money. In other words, we constantly think about whether we should buy something at X price, how much we need to budget, and if we can spend Y dollars on Z things. All of these daily-tactical monetary decisions make us believe we are thinking about money, but we really aren’t.

The closest analog I have to how we think about money is system 1 and system 2 thinking (if you’ve never heard of this type of thinking, then please read the link above or read Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking Fast and Slow). In The Psychology of Money, Housel mentions that he attended an event where Kahneman spoke and references the insight he learned from hearing from the foremost teacher of behavioral psychology.

We constantly think about money in a heated state, but we rarely — if ever — think about money in a calm-collected-logical state. In many ways, money is a subject where it is difficult for our system 2 to impact our system 1. While everyone essentially understands the basics when it comes to money, very few of us actually adhere to it in our day to day lives (system 1):

- Be patient

- In order to earn you have to learn

- Save for a rainy day

- Budget so you have retirement funds

- Invest wisely and carefully

- Your net worth is not your self worth, from Toni Morrison

- 1. Whatever the work is, do it well—not for the boss but for yourself.

- 2. You make the job; it doesn’t make you.

- 3. Your real life is with us, your family.

- 4. You are not the work you do; you are the person you are.

- Your network can be tied to your net worth

The Psychology of Money delves into important system 2 topics and helps explain why our system 1 completely hijacks what we actually do with our “hard-earned dollaz.” Housel has thought a fair bit about money and he opens the book tongue in cheek by identifying the paradox-conundrum that even though we think about money a lot we really don’t think about the meta and the most critically important aspects of money: “The world is full of obvious things which nobody by any chance ever observes.” – Sherlock Holmes

Having attended what is thought of as one of the more “prestigious or preeminent” churches of capitalism/Mammon (Stanford’s Graduate School of Business), I can say first-hand that very little of what Housel writes on was ever discussed at the school. That’s unfortunate. The school does a good job of teaching its disciples the mechanics and tactics of making money (marketing, accounting, finance, managing people, negotiations, etc…) but doesn’t have any course on how to think about money. The business school is an excellent trade school for learning about how to move money efficiently but not about how to think about money:

- Is it important?

- What should we do with money?

- Why do we want money?

- How much is enough money?

- What is more valuable than money?

Housel notes that the lack of meta-thinking about money is something that affects all of society: “We think about and are taught about money in ways that are too much like physics (with rules and laws) and not enough like psychology (with emotions and nuance.)”

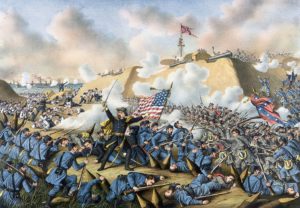

Almost all specialized schools are adept at teaching the mechanisms but not the meta-aspects of a topic. Similarly, West Point does a decent job of teaching about the military (infantry tactics, leadership, military training, civil-military relations, etc…) but devotes little to no time on equally important topics of:

- Why do we have a military?

- How large should the military be?

- What should we use the military to accomplish?

- How much spending should be devoted to the military?

We won’t spoil the book but we will highlight a few phrases that should prompt-motivate people to spend their valuable time reading and reflecting on Housel’s ideas and writing:

- “The premise of this book is that doing well with money has a little to do with how smart you are and a lot to do with how you behave. And behavior is hard to teach, even to really smart people.”

- “People do some crazy things with money. But no one is crazy.”

- “Spreadsheets can model the historic frequency of big stock market declines. But they can’t model the feeling of coming home, looking at your kids, and wondering if you’ve made a mistake that will impact their lives.”

- Housel examines and adeptly explains why people who don’t have much money buy lottery tickets.

- The importance of one’s personal background and how they think about using-spending money (or as people on earning’s calls like to say, “capital allocation”).

- “[An] important point that helps explain why money decisions are so difficult, and why there is so much misbehavior, is to recognize how new this topic is…. We’re not crazy. We’re all just newbies….There is not decades of accumulated experience to even attempt to learn from. We’re winging it.”

- Housel’s letter that he wrote to his son after he was born is essentially identical to the opening lines of Great Gatsby: “In my younger and more vulnerable years my father gave me some advice that I’ve been turning over in my mind ever since. “Whenever you feel like criticizing any one,” he told me, “just remember that all the people in this world haven’t had the advantages that you’ve had.”

- How many people feel like they just can’t get enough money and an interesting question posed from perhaps one of the best movies about Wall Street (and self-titled that way) and money with the line how much is enough?

- What’s more valuable than money? A list from Housel that I’d agree with: “Reputation is invaluable. Freedom and independence are invaluable. Family and friends are invaluable. Being loved by those who you want to love you is invaluable. Happiness is invaluable.”

- The importance of compounding and becoming one percent better every day

- Other important concepts that are obvious but nonobvious: there’s a thin line between success and failure. If you want to be wealthy, then you have to be healthy (alive and survive).

- There’s a price to success: a price of admission.

As I think about the book, I realize that money is very much a “religion.” Whether we like it or not. Many people pursue it and have an interest in it and ascribe supreme importance to it.

- There are set social-cultural values associated with money.

- It’s a very public and private act and there’s a lot of status associated with money.

- We unfortunately place a lot of social value to people with a lot of money.

- Like traditional religions, it’s something that is seen as really taboo to talk about among friends or among professional colleagues.

- In the Bible, it is described as a religion, the worship of Mammon.

The Psychology of Money is important because even though you don’t need to worship money, everyone else does. Hence, you need to understand and learn about it. And the Psychology of Money will help you better understand “money.” The book is very accessible, well written, interesting, insightful, includes pithy quotes, and I finished the book in 3-4 sittings over the weekend. I highly recommend this book (10/10) and even though I don’t gamble I’ll use this line: I’d put my money that this book will do really well. There are just not enough thoughtful books about how to think about money.

...